Review of Siciliana

I think entirely too much about Arthur Miller’s The Crucible and Shakespeare’s histories and Julius Caesar. I understand these classics are plays and not novels. But are they nonfiction? The characters are all named after real people who lived real lives and the dates match up. I suppose there is Great Caesar’s Ghost as a character, so it really can’t be regarded as nonfiction, but maybe historical fiction? As a creative nonfiction author, I ponder about this.

By Adam Faraca, who is Calabrese

6/20/20255 min read

I first heard the stories that came to be THE COLORS WE BLEED FOR in 2006 when I was grasping at straws to find any link between being an Italian American and Serie A. At the time I was not the author, creative mind, and storyteller that I am today. I knew the story, I just wasn’t ready to tell it. Plus I really thought some better author who was on the ground in Firenze would research it and knock it out of the park. There are academic works about that time and those people, but nothing that really tells the story in the way I wanted it to be told.

I’ve chatted with Carlo Treviso a couple of times, but I don’t claim to know him well at all. I know he’s a fellow Milwaukee native and a Sicilian. That’s most of what I know about him. He wrote a novel about Sicily in the 1200s that is inspired by true events. I wrote a novel about Italy and Italian Americans in the 1900s, which I have submitted specifically as a nonfiction novel. We’re both removed from our settings, though mine is about a hundred years instead of closer to 800. It is amazing to me that there is another Italian American Milwaukeean out there writing about history and culture in a meaningful way that preserves our culture in a way that is entertaining and fun rather than just dry history.

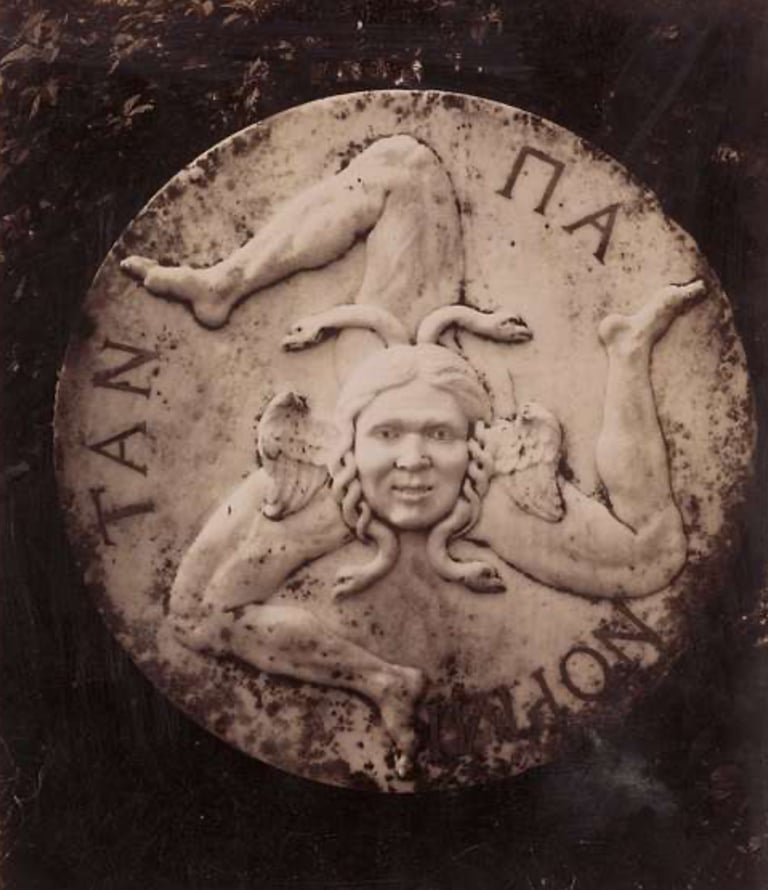

Carlo begins with a preface about wanting to share more about Sicilian culture than mafia romanticizing. “The M-word” as he calls it. Which I totally get. I actually had a piece of early feedback for my own work that a reader was pleasantly surprised to read something Italian that didn’t involve “the M-word.” It is refreshing to read something about Sicily that is not about the mafia and does a deep dive into life before the 1851 unification of Italy.

As I read, the unification of Italy kept popping up in the front of my mind. While Italy is a republic and has democracy, it is also a cultural confederacy, and in the sense that limiting the power of the federal government after Mussolini is a key component of their government, it is in many ways also a practical confederacy. It is a cultural confederacy in the sense that the phrase ‘100 years is no time and 100 km is an incredible distance’ applies to an extreme degree. Go to Florence, Rome, Naples, Milan, or Palermo. You might as well be in a different country every time you set foot in a different medium to large Italian city. You see that in America with Italian Americans, too. Sicilian Americans have some traditions, Neapolitan Americans have other traditions, and diaspora from the North have other traditions, too. We share a common culture and ancestry, but we have enough unique traditions and idiosyncrasies to fill a set of encyclopedias. Siciliana is, not surprisingly, Sicilian.

Siciliana begins with violent rebellion and the desire to self-govern in a contained kingdom that is an island. There is an extended flashback that demonstrates how an independent agrarian class exists more or less in isolation on the island, but international trade and foreign nobility prevent the native Sicilians from thriving. You can only hold down and oppress people for so long… a lesson that the foreign ruling class soon learns the hard way.

The book is essentially a modern telling of myth, which I like a lot. There are kings, bishops, knights, peasant rebellions, and it has a sort of Sicilian Game of Thrones vibe. You have a bunch of poor people living on an island in the shadow of a volcano, and political and economic tension create a pressure cooker. The narrative goes back and forth from Aetna, the central protagonist, to her father, who is something of a legend, himself. As the book progresses, there are other male and female POV characters. I have to give Carlo Treviso credit, writing a book about a female protagonist in a male-dominated culture, as a male, is no small task. Carlo is more than up to it.

The extended sequence of the rebellion played out similar to the social upheaval at the end of Martin Scorsese’s Gangs of New York. Violence and class conflict spread like wildfire, and nobody in the ruling class is safe. The grisly violence of the unrest is not sugar-coated, like at all. I don’t claim to be an expert or historian of Sicily as a kingdom or fiefdom in the Middle Ages, but I assume the way Carlo Treviso describes it is close to exactly as it would have been. One thing I particularly like is that it doesn’t follow the Disney storyboard. The hero must overcome adversity, but it is not like she is humiliated or humbled and has a training montage and comes back stronger to save the day. Nope. The moment presents itself and she seizes it. Straight and to the point.

One of the subtle things that really works well is the syntax of the sentences. It reads like a text written down after hundreds of years of oral tradition. Carlo Treviso achieves that quality throughout and it is not an easy thing to do. It is almost like writing or translating the Iliad or Aeneid a couple of thousand years later. What is even more impressive is that the oral story finally put to page aspect is accentuated by the use of authentic Sicilian dialect. Like most Italian Americans, I learned Florentine in Italian language classes, while learning Calabrese phrases at home. Dialect and jargon make the story real.

I almost never read fantasy. I appreciate the challenge of world building and then creating compelling characters within that world, but I just don’t delve into fantasy very often. Siciliana has to world build and create compelling characters to work as a novel. Being it is a real place, with real people and culture, and a real history, the world that is built is one that actually existed and is easy to imagine. It is not some other planet, or imaginary kingdom, it is real and it comes alive in the novel. It is almost like an Italian King Arthur, with less fantastic noble quests and more grounded reality. Well done.

I hate dry, boring history. I’m also not a huge fan of grandiose national myths from like thousands of years ago. But I also enjoy books and stories that exist to preserve culture and give readers a broader understanding. One thing I particularly enjoyed about Siciliana is that the narrator has a modern voice that makes it easy to read. The book is imperfect, as all books are, but it doesn’t really matter because the narrator keeps the train on the tracks while the reader is engrossed in a wild ride.

There are tons of details that bring it all together. I feel like I must have missed a ton of little things, and that it has re-readability for days. It is great to read a period piece that is not knights from France or Great Britain as the good guys. This is conjecture, but I bet Carlo is developing it into a movie. I hope he does. And there are recipes at the back of the book. If you want something entertaining instead of rereading Lord of the Rings or The Sicilian, pick up a copy of Siciliana, you’ll be glad you did.